Martin Kramer, “Ambition, Arabism, and George Antonius,” in Martin Kramer, Arab Awakening and Islamic Revival: The Politics of Ideas in the Middle East (New Brunswick: Transaction, 1996), pp. 111-23.

An earlier version appeared in The Great Powers and the Middle East, 1919-1939, ed. Uriel Dann (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1988), pp. 405-16.

The world first learned the history of Arab nationalism from a book published in 1938. The Arab Awakening by George Antonius eventually became the preferred textbook for successive generations of British and American historians and their students. Yet few now would deny that The Arab Awakening, for all the appeal of its narrative style, is more suggestive of a sustained argument than a history.1 “I have tried to discharge my task,” wrote Antonius in the forward to his book, “in a spirit of fairness and objectivity, and, while approaching the subject from an Arab angle, to arrive at my conclusions without bias or partisanship.” But Antonius did not pretend that his work met the highest standards of the historian’s craft. The Arab Awakening he preferred to regard as the “story” of the Arab national movement, “not the final or even a detailed history.”2 And once the book was near completion in 1937, Antonius wrote that “my contribution should be one not merely of academic value but also of positive constructive usefulness.”3

In this practical bent, he was encouraged by the very practical American patrons who financed his researches and owned all the rights to the book. One of these insisted that the writing of The Arab Awakening “is not an end in itself, but only a means to an end.” It was

an open question just how many problems are solved by the propagation of knowledge. On the other hand, writing a book is an excellent means of establishing a reputation for yourself. It helps you to reach into certain groups which you need to get into intimate contact with, and it gives you authority. In this limited sense, therefore, writing is a useful adjunct to your activities.4

These more urgent pursuits required that Antonius transform himself from observer into participant. Antonius himself wrote that

my particular educational and vocational formation has fitted me to be above all a bridge between two different cultures and an agent in the interpretation of one to the other. I feel that this fitness, so far as it goes, enables me to be of use in the task of studying and understanding the forces at work in the Near East, and of putting my knowledge and understanding to good account both as an interpreter and a participant. That is what I feel to be my true vocation in life.5

The Arab Awakening, then, was written not only to advance an Arab nationalist argument but to establish a reputation in pursuit of a career. That career consisted of casting aside pen and paper and pursuing political influence in a brisk dash across the Middle East—a “short story” of self-immolation that strangely presaged Arabism’s own demise.

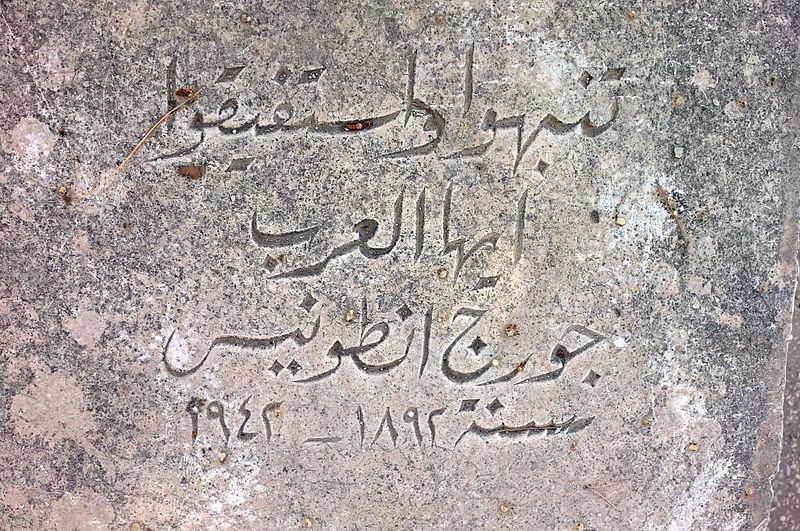

The Accidental Author

Antonius came late to authorship. Born in 1891 to Greek Orthodox parents in Lebanon, he had been raised in Egypt and schooled in England. After World War I, Antonius had found his niche in the civil service of Palestine, where he proved himself an able administrator in the education department. During the mid-1920s, he had experienced the exhilaration of high negotiations as an interpreter on loan to a British diplomatic mission in Arabia. Sir Gilbert Clayton, who headed the mission, treated Antonius as a partner and confidant—an experience that lifted Antonius above mundane administration and gave him a taste for politics.6

Still, it was only after his bureaucratic career had reached an impasse, in an acrimonious dispute over his advancement, that Antonius took up a pen. Had he wished, he could have joined his father-in-law, the publisher of a leading Cairo newspaper, who was eager to bring Antonius into his business. But a conventional career in Arabic journalism did not appeal to Antonius, and only briefly did he consider working as a reporter for the foreign press. For in 1930, an American newspaperman suggested to Antonius that he “do the Near East” for a new institute of international relations financed by a wealthy American, Charles Crane: “This is in general (financially and otherwise) far superior to any correspondent’s job; it is dignified and important and the work is useful. If you definitely are leaving the government I don’t think you could make a better arrangement than with Crane.”7 Antonius took a leave of absence and sailed for New York, where he signed an agreement with Crane’s major-domo establishing Antonius as a fellow of the Institute for Current World Affairs (ICWA). His obligations over the next decade included researching and writing his book and accompanying Crane during the American’s annual peregrinations in the region.8

Some who met Antonius during this decade thought him a man devoted to intellectual pursuits and committed to scholarship. He seemed preoccupied with the writing of his book, he corresponded with Western historians and orientalists, and he lectured at universities. His occasional forays into politics, wrote one admirer, “were all examples of people asking George to do something, not of his initiating anything. He was the exact opposite of a busybody. The sort of thing which he did take the initiative in was the big intellectual enterprise like the Arabic lexicon or an Institute of Arabic Studies. It was only occasionally, when a particularly glaring political gap presented itself, that he was moved to intervene.” Others sought his mediation in their disputes, but “he did not himself seek the role.”9 Here was an assertion that only the most pressing of political exigencies could divert a reluctant Antonius from his scholarly pursuits.

But did Antonius welcome an academic career and the opportunity to pursue his work single-mindedly? In 1936, as The Arab Awakening neared completion, Crane learned that Columbia University sought to replace the recently deceased Semiticist Richard Gottheil. Crane immediately wrote to Nicholas Murray Butler, Columbia’s president, to propose Antonius as a possible successor. Antonius “is still in the early forties,” wrote Crane, “and might have a long and distinguished career at Columbia.”

He is of a fine old Greek family but says he cannot remember the time when he did not speak Arabic and French. He not only knows classical Arabic as well as any Arab, but speaks some ten or a dozen dialects of it. He has his doctor’s degree both from Oxford and the Sorbonne. His English is quite the best Oxfordian. . . . As he is neither Jew nor Arab he is untouched by the deepest racial problems and carries very successfully an objective outlook.10

Antonius had not expressed any interest in departing so completely from his prior course. Nor could Antonius present the proper credentials, for he held no doctorate, either from Oxford or the Sorbonne, but had only a bachelor’s degree in mechanical science from Cambridge. Yet Butler, perhaps too eager to satisfy so prominent and wealthy a figure as Crane, offered Antonius a visiting professorship for the 1936-37 academic year, in order to allow Columbia to take his measure. Antonius would not be expected to do any formal teaching, but would consult with students and faculty and would “help us to formulate our plans for the continuation of our work in Oriental languages and literatures.”11 The ICWA cabled this remarkable offer to Antonius in Jerusalem.

It would be idle to speculate how Antonius, atop Morningside Heights, might have influenced America’s emerging vision of the Middle East. For Antonius did not wish to parlay The Arab Awakening into an academic position. He bombarded New York with cables asking for detail after detail on the responsibilities he would be asked to bear at Columbia, and the academic year began without him. Had he acted more decisively, Antonius might have thwarted an effort by Gottheil’s widow and Jewish alumni to have the invitation to Antonius withdrawn. They were quick to point out to Butler that Antonius already had a reputation among Zionists as an Arab propagandist, and that Crane’s representation of Antonius as “neither Jew nor Arab” widely missed the mark. Since Antonius had procrastinated, an embarrassed Butler still could retract the invitation without too much loss of face, once controversy loomed.12 This episode, which reflected little credit upon any of the parties involved, underlined Antonius’ ambivalence about the prospect of a career in scholarship, far from the political fray. Not for this had he labored.

In anticipation of the publication of The Arab Awakening in 1938, Antonius was summoned by his American patrons to formulate a program of further research. To the ICWA, he suggested a new program of study that committed him to a busy schedule of writing and publishing. He vaguely proposed to write “a comprehensive survey of my area,” a project which he estimated would require five years to complete. At the same time, he would prepare some half dozen articles for publication each year.13 But over two years later, the theme of this sequel still had not “taken final shape yet, not even in my mind. But the general lines are as I have already written to you, that it will take the form of a commentary, with examples drawn from the current problems of the countries of my area, on the moral and social issues which confront the world today.”14 There is not the slightest evidence in Antonius’ own voluminous papers that he ever began to plan such a study.

“Suitable Work”

If not a sequel, then what further pursuit appealed to Antonius? He briefly considered working as a paid advocate of the Arab case in London. As early as 1935, Antonius was reported to be “keenly interested” in the establishment of an Arab information office in London. But in his view, “the question of the expense and the financial support of such an office would be too important to be undertaken by only one party, and the mutual sharing of expenses by all parties would be out of the question, since no person equally trusted by the several mutually antagonistic groups could be found.”15 Nor did it seem likely that the remuneration could match his ICWA allowance, which was both ample and dependable.

Later, in January 1939, Antonius arrived in London to serve as secretary to the Arab delegations at the Round-Table Conference on the future of Palestine. This signaled his return to high politics, and one of his British opposites found him “a hard and rather pedantic bargainer” on behalf of the Arabs.16 According to a British source, Palestinian Arab nationalist leaders even suggested that Antonius

stay in London to look after the Arab Centre. He anticipated that this meant that the [Arab] Committee in Beirut were contemplating increased Arab propaganda in London. He would rather not accept this post until he had had a chance of learning their mind by travelling to the Near East, but he thought it quite possible he would return.17

But this, too, was not precisely what Antonius had in mind. Open identification with the Arab information effort would have made him an overt partisan and disqualified him from a further role as mediator and possible participant. Instead, he returned to the Middle East, where the anticipated outbreak of war seemed likely to provide him with an opportunity, as war had done for him twenty-five years earlier.

This time, it appeared to Antonius that his opportunity would arise in Beirut. There, in late 1939, he took a furnished flat, explaining that “while the war lasts there does not seem much to choose between residence in Beirut, Jerusalem or Cairo, save for the fact that the first is appreciably cheaper than either of the others.” In April 1940, he reported that he did visit Cairo and Jerusalem, “to discover whether there might be some advantage in shifting my residence,” but learned that “there is little to commend either as being preferable to Beirut.”18

Beirut at this time, while perhaps cheaper than the other two cities, was also the site of considerable intrigue, the work of exiled Palestinian Arab nationalist leaders and local clients of rival European powers. And there is ample evidence that Antonius began to seek out opportunities in this cauldron. From the middle of 1940, he began a quest for wartime employment, a fact which he belatedly confessed to the ICWA:

I have offered my services in turn to the French, the British and the American authorities in my area, and I offered them without restriction as to locality or scope save for two stipulations, namely (1) that the work to be entrusted to me should be in my area, to enable me to continue to watch current affairs for Institute purposes, and (2) that it should be constructive work in the public service and not merely propaganda.19

The instrument of this effort was a memorandum “which I have drawn up on my own initiative in the belief that the public interest demands it,” and which reviewed “the state of feeling in the Arab world in regard to the issues arising out of the conflict between Great Britain and the Axis Powers.” Antonius submitted it first to the British.20 The Arabs, Antonius maintained, were in a state of apprehension, “which is all the more striking as it is grounded not only upon distrust of Italian and German assurances but also upon uncertainty as to British and French intentions in respect of the political and economic future of those countries.” The Arabs, then, were wavering, although in a cover letter Antonius made a protest of loyalty on his and their behalf. He himself believed in the value of Anglo-Arab collaboration,

not only for its own sake but also as a means toward the upholding of those principles of freedom and the decencies of life, in the defence of which Great Britain is setting such a gallant example. My knowledge of Arab affairs enables me to state, with the deepest conviction, that the Arabs are at heart as attached to those principles as any other civilized people.21

He also determined that “there are throughout the Arab world an underlying preference for Great Britain as a partner and a willing recognition of the benefits that have accrued to the Arab countries from their past association with her.”22 (This was a very different approach from that which he had employed in the Round-Table Conference little more than a year earlier. There, speaking of the Italians, “who were always very friendly to the Arabs,” he had warned that while he “did not wish his delegation to put themselves in the hands of any foreign Power,” Great Britain “must not tempt them too much by being intransigent over the terms of our settlement.”)23

The Arabs preferred Great Britain, claimed Antonius, but in order to secure active Arab collaboration, Great Britain necessarily would have to offer certain guarantees. This time there would be no secret pledges or covert undertakings of the kind Antonius had dissected in The Arab Awakening. Great Britain would issue a unilateral “enunciation of principles defining the attitude of the British Government towards Arab national aims,” supporting the independence and unity of the Arabs, and among them the Arabs of Palestine. Then Antonius made this proposal, drawn from the experience of the previous war, and not without due consideration of his own predicament:

I am of the opinion that there is a pressing need for the creation of a special British bureau in the Middle East, whose main functions would be to attend to political and economic problems in the Arabic-speaking countries. The most suitable location for the bureau would seem to be in Cairo, but it should have branches in Jerusalem and Baghdad, and possibly in Jeddah and Aden, and a liaison agency in Whitehall. The head of the bureau should be a personality of some standing to whom a high military rank might be given, and he would have to assist him a small staff of carefully selected men who have experience of Arab problems and contacts in the Arab world. One of the functions of the bureau would be to establish close and widespread contact with persons of all shades of opinion in the Arab world, with a view to keeping its pulse on the movements of ideas, the reactions to military events and to Axis propaganda, the hardships caused by economic dislocation and the underlying grounds of discontent. Another function would be to put the knowledge thus collected to good use by studying possible remedies and devising practical suggestions.

Once armed with “all the relevant information,” this agency would be in a position to make “comprehensive recommendations” as to the action required.24 It was no doubt in connection with such a bureau, fulfilling precisely those tasks for which he felt himself uniquely gifted, that Antonius envisioned his own employment.

Antonius showed a draft of the memorandum to the high commissioner for Palestine, Sir Harold MacMichael, who saw through it. The document, he noted, “suffers from a touch of intellectual dishonesty, coupled, perhaps, with a certain lack of courage; neither is deliberate nor, I think, realised by the writer himself. The fact remains that the Memorandum is more of an essay by an ambitious writer, than a piece of constructive statesmanship.”25 At the Foreign Office, where evidence of Arab collaboration with the Germans and Italians accumulated at a rapid pace, readers of the memorandum found it “valueless” and “of little practical use.”26 As for Antonius himself, the British simply would not have him. According to an American who inquired after Antonius among British officials in the Middle East, they

did not trust Ant., because if put in an office he would be trying to run the whole office in a couple of days. While British recognize that he is in a sense anti-British with respect to Palestine, no one even suggests that Antonius is pro-Nazi with respect to the Arab movement as a whole. The lack of trust is simply on the point mentioned above, that he will be willing to fit in and cooperate, rather than run away with the whole show.27

The ambition which Antonius had borne within him was now common knowledge. And as the author of a book on British policy in the last war with all the character of an exposé, he could hardly be made privy to the formulation of policy in this war. If Antonius had any questions regarding the British assessment of his reliability, British frontier authorities answered by searching his person and taking his papers on one of his crossings into Egypt. “This was considered by A. an affront.”28

Antonius then offered his talents to the Americans. To Wallace Murray, chief of the Division of Near Eastern Affairs at the State Department, Antonius also had written a lengthy, unsolicited letter sketching the “trends of public opinion” among the Arabs, along with an offer of his services:

I am tempted to offer, if you should find this kind of letter of sufficient interest, to write to you again whenever my studies bring me to the point when I feel I can draw up useful conclusions. My address in Beirut is the Hotel St. Georges, but for the next few weeks I shall still be up in the hills. Perhaps the best way of getting a message to me would be to send it in care of the Consulate, with whom I am always in touch.29

This letter, virtually identical to his overture to the British but with recommendations for British policy removed, was apparently intended to evoke an American offer of employment. But the call from Washington never came.

Antonius had failed in his pursuit of an influential place in the Allied war machines. In November 1941, he wrote to the ICWA that “although I began offering my services over a year ago, I have not succeeded yet in finding some suitable work that would satisfy those two stipulations.” He had some reason to believe that a proposal “of an acceptable nature” would be made “at no very distant date,” but shared no details. There is no evidence in his papers for any Allied proposal of any kind.30

The Allies had spurned him, but Antonius would not relent. He now made a desperate bid to secure a place as an influential mediator between irreconcilable forces in Iraq. In April 1941 he arrived in the Baghdad of Rashid Ali al-Kaylani, where he appeared in the company of the exiled mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husayni. Antonius had an unqualified admiration for Haj Amin, who, as Freya Stark recalled, “had bewitched George Antonius as securely as ever a siren did her mariner, leading him through his slippery realms with sealed eyes so that George—whom I was fond of—would talk to me without a flicker about the Mufti’s ‘single-hearted goodness’.”31

By this time, Haj Amin and Rashid Ali had placed their trust in the Germans, and Haj Amin’s private secretary already had conducted negotiations in Berlin on precisely how to put an end to the British presence in the Middle East. But for Freya Stark, and through her the British Embassy in Baghdad, Antonius tried to put an entirely different face on events. Antonius “admitted he had heard in Cairo that Rashid Ali is in German pay—but even if this had been so in the past, it did not follow it need be in the future.” Antonius then proffered his services as a mediator.32 Could Antonius have been so unaware of the sea of intrigue whirling about him in Baghdad that Rashid Ali’s German links were known to him only by Cairo rumor? He supposedly wrote an account of the Baghdad events, but it does not survive.33

Antonius felt the first effects of a duodenal ulcer in Baghdad, and he returned to Beirut a sick man, a few weeks before the British campaign which purged Iraq of his associates. Things did not go well in Beirut:

Shortly after, my persecution by the Vichy French and the Italian Commission began. At first they wanted to expel me, and later to put me in a concentration camp. It was only my illness in hospital and the intervention of the American Consul General (Engert) that saved me from the worst effects of that persecution.34

A short time later, Antonius returned to Jerusalem, thwarted and ill. He had failed in his pursuit of a kind of influence for which The Arab Awakening did not constitute a credential. And so thoroughly had he neglected to report his activities and submit expense accounts that the ICWA’s director and trustees began to plan his dismissal.

As early as August 1940, the ICWA’s director had approached the Department of State to offer that “if Mr. Antonius’ connection with his organization was likely to be in any way an embarrassment to the Department he would wish to dissolve the connection without any delay.” American diplomats had no ill words for Antonius. But according to an American official, the ICWA’s director still was “on the lookout for a young American who might be sent to the Near East to learn Arabic and who might eventually be in a position to serve as the Institute’s principal representative in that area. He added that he would appreciate it if we would recommend to him any promising young American with an inclination to Near East Studies who might come to our notice.”35 Antonius had misjudged his employers, who feared that his political activities, about which he now told them next to nothing, might bring their work into disrepute.

Over a year later, their patience ran out. “The trustees of the Institute,” wrote its director to the ICWA’s lawyers,

have a high regard for Mr. Antonius and wish to deal fairly with him, yet they have responsibilities that cannot be disregarded, especially in such conditions as now prevail. After all, he is not an American and he is in one of the most highly charged areas of the world. So in view of his failure to keep in close touch with the office and be frank about his conditions and affairs, they have deemed it inadvisable to continue to finance him.36

The result was to leave Antonius financially embarrassed, and he wired New York repeatedly, demanding money and a reversal of the ICWA’s decision. “When I decided to give up my career in the public service in 1930,” complained Antonius, “I did so on the understanding that our agreement would be a permanent one, and that it was not liable to be terminated without valid cause. It is not easy at my age and in the midst of a world war to embark on yet another career.”37 The plea was disingenuous: Antonius had longed for another career ever since the publication of The Arab Awakening. But now he was without any employment at all, and had reached an impasse. As it happened, a complication of his illness claimed Antonius before idleness or debts, in May 1942. “Poor George Antonius,” wrote Stark, “a gentle and frustrated man and my friend, was dying too, and soon lay in Jerusalem in an open coffin, his face slightly made up, in a brown pin-stripe suit, defeating the majesty of death.”38

Of the later career of George Antonius, it can only be said that it showed more the effects of his ambition than his patriotism. He never doubted that he was too large for the clearly subordinate role suggested to him by Arab nationalist leaders, who would have kept him as a propagandist in London. His vain sense of “true vocation” would not concede that he had served his cause best as an author, and might serve it still better in a great university or in yet another book. To sit, pen in hand, even in the cause of an Arab Palestine, was a form of exile, which ended in a blind pursuit of political influence. And so the poet Constantine Cavafy’s celebration in verse of the Syrian patriot is really most evocative near its conclusion:

First of all I shall apply to Zabinas

and if that dolt does not appreciate me,

I will go to his opponent, to Grypos.

And if that idiot too does not engage me,

I will go directly to Hyrcanos.At any rate, one of the three will want me.39

© Martin Kramer

Notes

1. The book has seen many reappraisals, the most important by Sylvia Haim, “‘The Arab Awakening’: A Source for the Historian?” Welt des Islams, n.s., 2 (1953): 237-50; George Kirk, “The Arab Awakening Reconsidered,” Middle Eastern Affairs 13, no. 6 (June-July 1962): 162-73; Albert Hourani, “The Arab Awakening Forty Years After,” in his Emergence of the Modern Middle East (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981), 193-215; and Liora Lukitz, “The Antonius Papers and The Arab Awakening, Over Fifty Years On,” Middle Eastern Studies 30 (1994): 883-95.

2. George Antonius, The Arab Awakening: The Story of the Arab National Movement (London: H. Hamilton, 1938), 11-12.

3. Antonius (New York) to Walter Rogers (New York), 28 May 1937, file labeled “Antonius: Correspondence, Reports vol. II 1934-43,” Institute for Current World Affairs Archive, Hanover, N.H. (hereafter cited as ICWA Correspondence).

4. John O. Crane (Geneva) to Antonius, 14 October, 1931, George Antonius Papers, Israel State Archives, Jerusalem (hereafter cited as ISA), file 65/854. John Crane was the son of Charles Crane, Antonius’ patron, on whom see below.

5. Antonius (New York) to Walter Rogers (New York), 28 May 1937, file labeled “Antonius: Post-Staff Correspondence,” Institute for Current World Affairs Archive (hereafter cited as ICWA Post).

6. On Antonius’ earlier career in government service see Elie Kedourie, Nationalism in Asia and Africa (New York: World Publishing, 1970), 86-87; Bernard Wasserstein, The British in Palestine: The Mandatory Administration and the Arab-Jewish Conflict 1917-1929, 2d ed. (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), 183-89; Liora Lukitz, “George Antonius, the Man and His Public Career: An Analysis of His Private Papers” (in Hebrew; master’s thesis, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1978); Susan P. Silsby, “Antonius: Palestine, Zionism, and British Imperialism, 1929-1939” (Ph.D. diss., Georgetown University, 1985), 1-89; and idem, “George Antonius: The Formative Years,” Journal of Palestine Studies 15, no. 4 (summer 1986): 81-98.

7. Vincent Sheean (Sacramento) to Antonius, 21 January 1930, ISA, file 65/1961.

8. Text of seven-point agreement signed by Antonius and Walter Rogers, dated 9 April 1930 at New York, in ICWA Correspondence. The terms, generous by the standards of the day, stipulated a $7,500 personal allowance per annum, $2,500 in traveling expenses outside Palestine, and office expenses of up to $1,500 per annum.

9. Thomas Hodgkin, “George Antonius, Palestine and the 1930s,” in Studies in Arab History: The Antonius Lectures, 1978-87, ed. Derek Hopwood (New York: St. Martin’s, 1990), 86.

10. Crane (at sea) to Butler (New York), 12 June 1936, ICWA Correspondence.

11. Frank D. Fackenthal (New York) to Crane (New York), 28 July 1936, ICWA Correspondence.

12. Butler (New York) to Antonius (Jerusalem), 6 October 1936, ICWA Correspondence. This episode is discussed in more detail by Menahem Kaufman, “George Antonius and American Universities: Dissemination of the Mufti of Jerusalem’s Anti-Zionist Propaganda 1930-1936,” American Jewish History 75 (1985-86): 392-95.

13. Antonius (New York) to Rogers (New York), 28 May 1937, ICWA Post, for original plan.

14. Antonius (Beirut) to Rogers (New York), 30 December 1939, ICWA Correspondence.

15. E. Palmer (Jerusalem), dispatch of 9 March 1935, National Archives, Washington, D.C., RG59, 867n.00/237.

16. L. Baggalay minute of 12 April 1939, Public Record Office, London (hereafter cited as PRO), FO371/23232/E2449/6/31. According to Antonius, his appointment was the idea of Iraqi prime minister Nuri Pasha, whose suggestion enjoyed British support; Antonius (London) to Rogers (New York), 15 February 1939, National Archives, RG59, 867n.01/1466. For more on the role of Antonius at the conference, see Silsby, “Antonius,” 242-92.

17. Memorandum of conversation by L. Butler on meeting with Antonius, 30 March 1939, PRO, FO371/23232/E2379/6/31. But Antonius “did not think very highly of the work of the Arab Centre. He thought that they had made some useful contacts with M.P.s in London, but that the ‘atrocity’ propaganda of the Arab Centre was a deplorable blunder.” Memorandum of conversation by Downie on meeting with Antonius, 31 March 1939, PRO, FO371/23232/E2449/6/31.

18. Antonius (Beirut) to Rogers, December 30, 1939; Antonius (Cairo) to Rogers, 11 April 1940, ICWA Correspondence. His home in Jerusalem was not a consideration, for Antonius, according to an American diplomat, had “separated from his wife who is living in their house here.” G. Wadsworth (Jerusalem) to Wallace Murray (Washington), 5 October 1940, National Archives, RG59, 811.43 Institute of World Affairs/15.

19. Antonius (Beirut) to Rogers, 25 November 1940, ICWA Correspondence.

20. Cover letter from Antonius (visiting Jerusalem) to High Commissioner for Palestine, 3 October 1940; and “Memorandum on Arab Affairs” of same date; both in PRO, FO371/27043/E53/53/65.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Memorandum of conversation by L. Butler on meeting with Antonius, 30 March 1939, PRO, FO371/23232/E2379/6/31.

24. “Memorandum on Arab Affairs,” PRO, FO371/27043/E53/53/65.

25. H. A. MacMichael to Secretary of State for Colonies, 7 October 1940, PRO, FO371/27043/E53/53/65.<

26. Minute page, PRO, FO371/27043/E53/53/65.

27. “Practically stenograph” of talk between McEwan and ICWA Fellow Samuel Harper, in letter from Harper (Chicago) to Rogers, 22 July 1941, ICWA Correspondence. Harper reported McEwan as saying that Antonius was “evidently living well and comfortably at the home of the wife of former president of Lebanon as I recall description of this aspect.”

28. Ibid.

29. Antonius (visiting Jerusalem) to Wallace Murray, 4 October 1940, quoted at length in letter from Murray (Washington) to Rogers, 2 November 1940, ICWA Correspondence.

30. Ibid.

31. Freya Stark, The Arab Island: The Middle East, 1939-1943 (New York: Knopf, 1945), 159.

32. Freya Stark, Dust in the Lion’s Paw: Autobiography, 1939-1946 (London: Murray, 1961), 79-80.

33. Antonius (Jerusalem) to John O. Crane, 12 February 1942, ICWA Correspondence, reports that he had sent a “long account” of his month in Baghdad to Rogers, “but I don’t think it could have reached him.” It did not.

34. Antonius (Jerusalem) to John O. Crane, 12 February 1942, ICWA Correspondence.

35. Memorandum of conversation with Rogers by J. Rives Childs, 14 August 1940, National Archives, RG59, 811.43 Institute of World Affairs/11.

36. Rogers (New York) to M. C. Rose of Baldwin, Todd & Young (New York), 21 May 1942, ICWA Correspondence.

37. Antonius (Beirut) to Rogers, 25 November 1941, ICWA Correspondence. Twenty years after the event, Antonius’ widow wrote that in 1940-41, Antonius could not correspond as he was “under strict surveillance from the French Vichy Sûreté. I believe Mr. Rogers wrote in a way which very much disturbed George and he resigned from the Institute—as he said—because he could not send the reports to the Institute.” As to Rogers’s attitude toward Antonius, “I felt it had added to his premature death.” Katy Antonius (Jerusalem) to Richard Nolte (New York), 9 January 1962, file labeled “The Arab Awakening,” Institute for Current World Affairs Archive. In fact, Antonius stopped filing regular reports before his move to Beirut and the fall of France, and his services were terminated against his protest. Within the ICWA, it was Rogers who had always been the most concerned about the political activism of Antonius, which he had tried to check a decade earlier; see Silsby, “Antonius,” 115-18.

38. Stark, Dust in the Lion’s Paw, 129.

39. “They Should Have Cared,” in The Complete Poems of Cavafy, trans. Rae Dalven (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976), 163. Cf. the verses of the poem quoted by Hourani, “The Arab Awakening Forty Years After,” 214-15.

You must be logged in to post a comment.