This is a perfect opportunity to remind readers that since the last Martin Luther King Day, I solved the mystery of this quote attributed to him: “When people criticize Zionists, they mean Jews. You’re talking anti-Semitism!” Some pro-Palestinian polemicists claimed he couldn’t possibly have spoken these words where he was supposed to have said them, at a dinner in Cambridge, Massachusetts, not long before he died. I succeeded in establishing a date (October 27, 1967), a street address (20 Larchwood Drive), and a time of day (early evening) for the occasion. Go here for the full story.

And while I’m at it, I’ll solve a mystery-in-the-making. In honor of the day, the Israel State Archives has published a batch of Israeli documents, from the mid-1960s, about a possible visit by King to Israel. It’s fascinating material, and I commend my friend Yaacov Lozowick, the State Archivist, for taking this initiative (and others) to bring official documents to a wider public. But this cache, as Yaacov notes, leaves a question hanging.

In a nutshell, the Israelis thought it would be a fine idea to host MLK in Israel, and the more important he grew, the more convinced they were that it was something they should make happen. King, from his side, kept on saying all the right words, but kept on not coming. Those are the facts. What do they mean? Hard to say. Read the publication and see if you find an answer.

Of course, if the answer had been there, Yaacov would have found it already. The answer lies elsewhere, and it’s perfectly clear.

First, in 1966, King did enter an agreement to lead a Holy Land pilgrimage. King’s assistant, Andrew Young, visited Israel and Jordan in late 1966 to do advance planning with Jordanian and Israeli authorities. The pilgrimage was rumored to be in the works from that time, and on May 15, 1967, King announced the plan at a news conference, reported by The New York Times the following day.

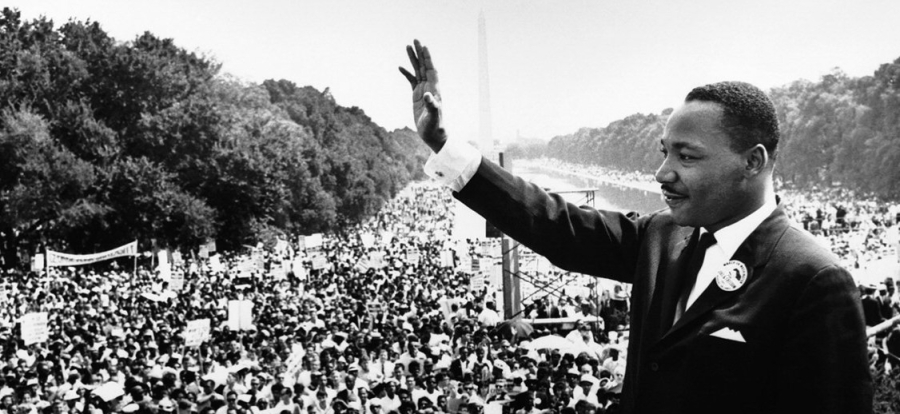

The pilgrimage would take place in November, and King insisted that it would have no political significance whatsoever. The organizers hoped to attract 5,000 participants, with the aim of generating revenue for King’s Southern Christian Leadership Council. King was slated to preach on the Mount of Olives in Jordanian East Jerusalem (November 14), and at a specially constructed amphitheater near Capernaum on the Sea of Galilee in Israel (November 16). The pilgrims would pass from Jordan to Israel through the Mandelbaum Gate in Jerusalem. King had visited the Jordanian side of Jerusalem in 1959, so he knew the situation on the ground, and thought he could strike just the right balance between Israel and Jordan. (The photo above depicts King and the Rev. Sandy Ray, pastor of a Baptist church in Brooklyn, who initiated and promoted the pilgrimage. King is pointing to the Holy Land on the map.)

The June 1967 war threw a wrench into the plan. King was now being asked his opinion of the war and Israel’s territorial gains. His position on both was complex, and perhaps I’ll go into it in a future post. But for now, let’s focus on the pilgrimage. After the war ended, Ray was still keen on going forward, and he immediately sent his own tour agent to Jerusalem to get a read on the situation. She came back enthusiastic: “I firmly believe that Dr. King’s visit will prove to be a much more historic event then we ever dreamed possible. Everyone, from the Governments down to the people on the streets were asking me about Dr. King… We desperately need a new Press Release from Dr. King reaffirming the Pilgrimage plans.”

So what happened? King got cold feet, and this isn’t a guess. We have it right from King himself, in the FBI wiretaps of one of his advisers, Stanley Levison. In a conference call of King and his advisers, on July 24, 1967, King noted that the responses to the pilgrimage promotion had been “fairly good.” (Andy Young said about 600 people had sent in deposits.) But if King went to the Middle East, “I’d run into the situation where I’m damned if I say this and I’m damned if I say that no matter what I’d say, and I’ve already faced enough criticism including pro-Arab.” He had met a Lebanese journalist who told him that the Arabs now had the impression he was pro-Israel, and that “you don’t understand our problem or something like that. And I expect I would run into a continuation of this.” King asked for advice, but set this tone:

I just think that if I go, the Arab world, and of course Africa and Asia for that matter, would interpret this as endorsing everything that Israel has done, and I do have questions of doubt.

King added that “most of it [the pilgrimage] would be Jerusalem and they [the Israelis] have annexed Jerusalem, and any way you say it they don’t plan to give it up.” After some back-and-forth among his advisers, in which it was suggested that he balance an Israel trip with a visit to King Hussein in Amman or Nasser in Cairo, King announced that “I frankly have to admit that my instincts, and when I follow my instincts so to speak I’m usually right… I just think that this would be a great mistake. I don’t think I could come out unscathed.”

King procrastinated out of deference to Ray, who had laid out money on promotion of the pilgrimage. But on September 22, 1967, he wrote the following to Mordechai Ben-Ami, the president of El Al, which was to have handled part of the flight package:

It is with the deepest regret that I cancel my proposed pilgrimage to the Holy Land for this year, but the constant turmoil in the Middle East makes it extremely difficult to conduct a religious pilgrimage free of both political over tones and the fear of danger to the participants.

Actually, I am aware that the danger is almost non-existent, but to the ordinary citizen who seldom goes abroad, the daily headlines of border clashes and propaganda statements produces a fear of danger which is insurmountable on the American scene.

He ended by promising to revisit the plan the following year.

The cancellation took place a month before King attended that dinner in Cambridge. It adds another layer of context for his balancing act on the Middle East, of which his remark about Zionists, Jews, and antisemitism was but a piece.

Update, 2016: This post has been amalgamated into a larger published article on King’s approach to the Six-Day War, here.

(Below: Cover of the promotional brochure for the 1967 pilgrimage. Thanks to Düden Yeğenoğlu, who photographed it for me in the Andrew Young Papers at the Auburn Avenue Research Library in Atlanta.)